What is Anthropocene Risk? A Q&A with Patrick Keys

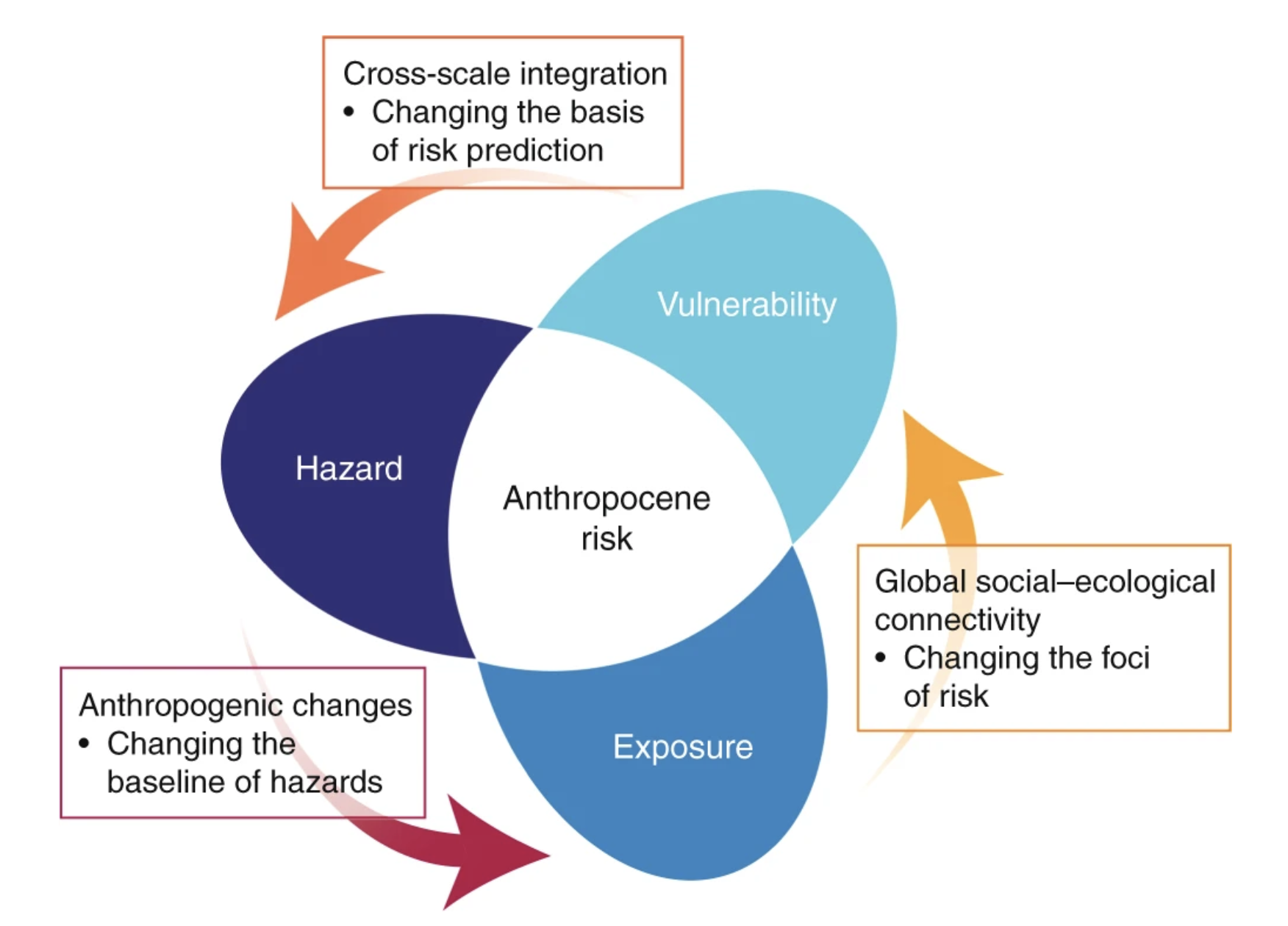

A new study in Nature Sustainability examines the complex nuances of Anthropocene risk, an integrated concept of systemic risk named after humanity’s dominating force on the planet’s geophysical, economic, and societal systems – and the unexpected consequences of their interactions. Or as they put it: “a new approach for characterizing unprecedented crises of the twenty-first century and beyond.”

This Perspective in Nature Sustainability was authored by Patrick Keys, a research scientist in the School of Global Environmental Sustainability at Colorado State University, a hosting institution of Future Earth. But it began during his post-doctoral fellowship with the Stockholm Resilience Center in 2017, as part of a larger project called Guidance for Resilience in the Anthropocene: Investments for Development (GRAID). Co-author Victor Galaz was Keys’ supervisor during that fellowship, and first introduced the term “Anthropocene risk” in a 2014 Guardian op-ed – but this is the first time it has been defined in a scientific context.

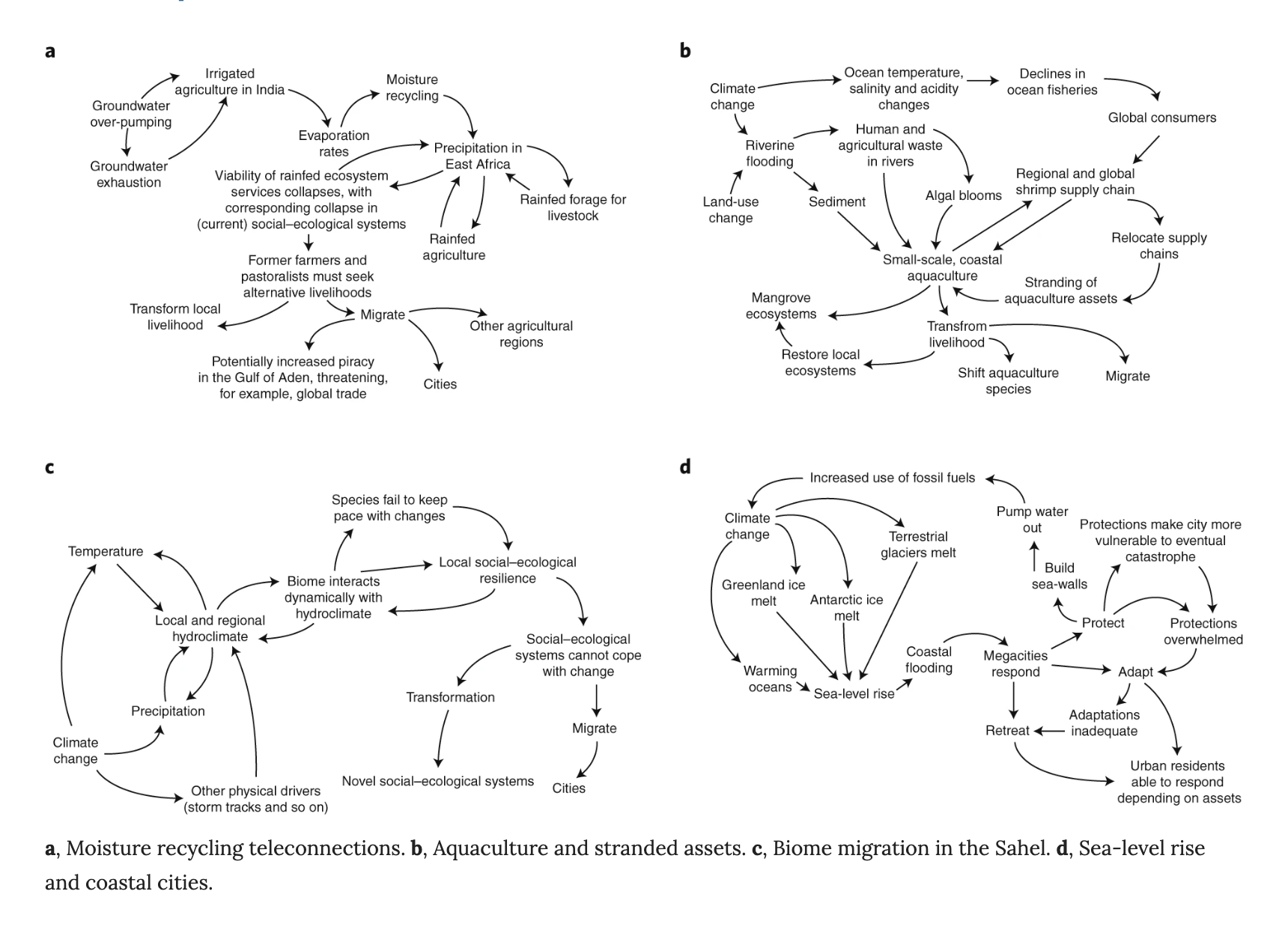

This paper introduces the concept of Anthropocene risk, its importance in relationship to current understanding of global systemic risk, and looks at four specific cases of Anthropocene risk: moisture recycling teleconnections, aquaculture and locally stranded assets, biome migration in the Sahel, and sea level rise and coastal cities. The paper also highlights the relationship between historical economic injustices and social inequalities and the present day power imbalances and exploitation of resources that have created many of these situations in need of examination through the lens of Anthropocene risk.

So far the paper has received coverage by Reuters, Colorado State University, the Stockholm Resilience Center, the World Economic Forum, and others.

We caught up with Keys to discuss some of the terms and concepts from the paper, and better understand the importance of examining Anthropocene risk in today’s world.

Kelsey Simpkins: Risk can mean something very different in different contexts. For example, in a daily life situation, it could be risky to do something. But how would you define risk in a more scientific context? And more specifically, how would you define systemic risk?

Patrick Keys: On a daily basis, everybody is constantly making risk calculations, right? Everybody’s brains are these little statistical machines. You look over your shoulder and think, can I merge right now? Can I make this turn? Am I going to be able to make it before this other car zooms up behind me? All of those are in some way like micro-risk calculations, but we don’t think of them that way. So those are straight-forward linear ways of thinking about a risk. What’s the risk to me and my family, if I don’t make this turn? And then if that calculation is too high, I don’t make that turn and wait.

Something that’s a little bit more complicated to stick with this traffic analogy, might be something like a big intersection where there’s lots of different things to pay attention to – things are getting a little bit more complicated than just, “can I make a turn?” So I like to distinguish between simple and complicated in that sense, because one is something you can reduce and the other requires a certain amount that you have to hold in your mind.

Complex risk, or systemic risk, is very different from those other two, simple and complicated, in the sense that there are elements of unpredictability or even chaos embedded in that system that you can’t fully reduce. And so because of that, you have to use different ways of understanding what those risks are. So take the risk of civil war onset in a country like Syria. You might have one thing that initially triggers a conflict, but you can’t say that that was the cause of the conflict, because there were lots of other things that led to that.

KS: The paper also talks about “globally connected systemic risks” and the fact that they potentially poorly capture this role of human and environment interactions. What’s that about?

PK: Part of the problem is that different communities look at different aspects of this sort of question. As a whole, it’s really challenging to try and consider some of these very long term interactions among social and geophysical systems. For example, the World Economic Forum, every year or two develops a global risks report. They survey what are the biggest global risks out there, and you can see that over time, the importance of environmental risks or environmentally related risks has steadily gone up over the last 10 years. Which is a way of saying that people who are in positions of power, business leaders, et cetera, are starting to consider those risks as more important than other risks over time.

A weakness of that approach is that it’s a survey of a relatively elite sector. Global world leaders have a particular interest set which will be very different than somebody who is not a business leader or “global thought-leader.” So when we look at a WEF-style report, it’s not necessarily representative of everybody in the world. It’s representative of those sectors.

Regardless, this is one example where an organization is doing a relatively good job of capturing how environmental risks are becoming a little bit more of a concern for those groups. While at the same time they might not be paying attention to things like the legacy of slavery on the dynamics of social environmental challenges in the United States. And that’s not to say that they don’t care about that. It’s just that the temporal frame that they approach these risks with – how far back do we need to be thinking about, about what is the risk, why does this risk exist? Those are some of the sorts of questions that we try start to probe a little bit more in our work.

KS: So you have this term of Anthropocene risk, which I would like to unpack a little bit. On the basic front you have it defined in the paper in some really explicit ways around risks that emerge from human driven processes, interactions with global social economic connectivity, and so on. But you can’t address the term Anthropocene risk without addressing the Anthropocene. Obviously with the recent piece in the Atlantic, this is not a completely finished discussion. But to you, what is the basic definition of the Anthropocene that you are using for this paper? And why do you think it matters to be able to talk about the Anthropocene?

PK: So I’m not a geologist. There’s a whole working group of people that study the definition of geologic eras, that are tasked with this definition process. And I trust that they’re doing a good job with that.

As far as the Anthropocene goes though, I think that conceptual notion of an Anthropocene, is this time where humans are changing the geophysics of our planet, the biology of our planet, the chemistry of our planet, the social fabric of our planet – we’ve been changing that for centuries and millennia. Of course we are a global force. When the paper was going through review, I think I said there was a statement in the paper that said something like, “we are the geologic force on the planet.” And then the reviewer said, “come on, that’s the sun.” The sun is of course the biggest geophysical force on the planet. But as far as we’re concerned on the time scales that we care about, humans have sort of taken over for a little while.

In terms of the dominant kind of possible change, we’re steering the planet towards a future that we don’t really know what it looks like. We have some very ancient analogs of in terms of millions of years ago. Some of those analogs have carbon concentrations in the atmosphere that look similar to what it might look like in our future. And so we can look back and say, okay, well what did that era look like? Do we want to live in a world that looks like that? And those are questions that can be answered.

As far as the Anthropocene goes, it is a useful conceptual touchstone for thinking about the fact that humans are changing the planet. At least for the future that we care about for the next couple hundreds of years, the fingerprint of humanity will be on the planet. Now, is that appropriate geologically to call it the Anthropocene? Like I said, that’s not up to me. I’m going to trust the experts. If they come back and say, we’ve got a new word then, okay, I guess we could use that new word. But honestly the Anthropocene has sort of left the geological dock. It captures the sustainability zeitgeist of our time.

And that’s the way that we try and use it in the paper. We adopt a science-based definition that could theoretically be tethered to a scientific question of anthropogenic influences on the planet.

To be clear, nobody is debating whether or not humans are having a profound impact on the planet. Pretty much everybody who is engaged in the Anthropocene categorization debate would also say, “Oh yeah, humans are totally impacting the planet in unprecedented ways. We just want to know whether or not there’s going to be some like thin layer of humanity, you know, 20 million years from now.” And so you sort of step back and go like, “Oh really? Oh, okay, fine.” And then you leave the room and let the geologists do their work.

KS: Why examine Anthropocene risk specifically?

PK: This research was intended to provide some sort of new theoretical framing or conceptual development for how we blend resilience ideas, such as social-ecological systems and cross scale interactions, into a more development-oriented focus. It was an opportunity to dig into this big topic of complex systemic risks. And then how does that world meet with some of these other topics: international development, social ecological systems, in new or surprising ways.

Lots of people have explored the nexus of those different fields together, and I’m pretty sure many of them are actually cited in our work. But the parallel interest set of mine has been this issue of power imbalances. You know, who gets to define what resilience is? Who gets to define what sustainability is? Who has defined it and is that still appropriate? Is it ethical? Is it right to have these people that are in this country over here defining what sustainability is and means? So this Anthropocene risk research was an opportunity to explore these dimensions explicitly.

KS: Why do you think other people haven’t explored that angle as much?

PK: I think part of the reason that it’s missing, is that it’s very difficult to actually include some of those dynamics and power imbalances. Everybody is constantly reducing things as much as possible, including reducing the complexity. Why would we want to add more complexity to this question? – which is what that would be doing. It would be saying that we can’t try and generalize and take the average of this system. We have to look at the distribution, especially the ends of that distribution, to better understand it.

With statistics, you can say that the world is getting better and yet the statistics also suggest that wealth gaps are widening. And understanding why those things are happening requires embracing complexity in a way that really is uncomfortable, because it forces us to not be able to use a simple average number to make a decision.

KS: How then does the Anthropocene present this novel challenge for you and understanding what risk means?

PK: One of the ways that the Anthropocene challenges our understanding of what risk is, is that a lot of risk, and even some resilience thinking – has some sense of returning to some prior state.

For example, we’ll experience a shock or a perturbation. And we’ll somehow mitigate that event, then wiggle our way back to our comfort zone, a place that we can be productive, happy, successful, do what we need to do. And by putting Anthropocene in front of risk, that invites people to say, no – we’re talking about entering an entirely new place. We’re entering a new world and new geophysical space and biological space and frankly a new social space, we’re entering a time and an environment that humanity has no collective understanding of what it means. If the world is four degrees Celsius hotter, that’s the average – which means it’s going to be way hotter on land. And we don’t have any experience of that, at least in a general collective sense.

When we talk about summertime temperatures in some places being above 150 degrees Fahrenheit – places that people live – we don’t have any memory or an adaptability baked into the system. And I think that our conventional notions of risk aren’t really capturing the fact that we are not where we need to be staying – where we are now – and that the world my two kids we’ll be living in is going to be profoundly different than the world that their grandparents grew up in.

And all of these different kinds of problems will start to cascade into one another: food security issues, water issues, energy issues, how much AC are we going to be consuming in the summertime in places that won’t have access to that energy? The combinatorial power of some of these problems is not captured well at all in some of these historic ways of reducing and describing risk, especially because the Anthropocene simultaneously is propelling our world forward. I mean for most of recorded history, humanity has reliably been able to count on the fact that things would more or less kind of bounce around conditions that generally, their grandparents or great grandparents had some sort of context for. I think that’s going to change for everyone in the next century.

KS: I found it interesting that in the first case study, it looks like the more efficient use of water in one area of the world might actually detrimentally affect another region in the future. Is that a good example of Anthropocene risk?

PK: In this example, we focus on India. For geophysical reasons that are simply a surprising feature of our planet, the evaporation arising in India is connected to the precipitation that falls in East Africa, during certain months of the year. This teleconnection is not Anthropogenic in origin, this is just the backdrop to an Anthropocene risk.

Changes in technology have allowed people all over the planet to access increasingly deep sources of groundwater. One consequence of this is to inject more moisture into the atmosphere. But if you’re taking water that would normally have stayed in the earth and then pumping it back out, that’s adding something to the system that probably wouldn’t have been added on that time scale. What we’re suggesting is that if India were to have some big change to their policy around this groundwater pumping, some communities in East Africa that have been adapting to this change from this groundwater might suddenly experience a change in their own system. And so even though India might be making a pretty good decision in terms of being good environmental stewards of their local environment, the fact of the matter is, is that given the scale of their impact so far, they’ve now almost connected themselves to another place. Parts of East Africa might now be subject to some negative impact. That’s not to say that India shouldn’t try and be more sustainable, but it does suggest that our typical reference points about what these types of connections might mean need to embrace complexity.

KS: In the fourth case study, you look at sea level rise. How is that so complicated, and therefore an Anthropocene risk?

PK: So we don’t know how quickly the oceans are going to rise, particularly since I feel like every single year we learn new things about how much more quickly the ice is melting. Ten years ago, it would’ve been pretty crazy for you to say a meter of sea level rise by 2100. And now people are just like, “oh yeah, a meter of sea level rise.” And it’s sort of like, “What? When did that change in attitude happen?”

But it’s not like our cities have suddenly started planning better. The 2018 National Climate Assessment, they included an extreme scenario of 2.4 meters of sea level rise by 2100. If we’re talking about risk, we need to be focused on those upper ranges. And we focus on cities and sea level rise, because from a social and economic perspective, they’re almost like the embodiment of Anthropocene risk.

KS: How so? How are cities like the embodiment of Anthropocene risk?

I want to say unnaturally dense concentrations of humanity could not be possible without all of the other modern trappings of society and kind of our contemporary life, a sewage waste disposal, reliable electricity and water, et cetera. This goes on. All of the things that define a modern society are what make cities possible, especially megacities. And importantly, for the most part, cities are remarkably persistent in space and time.

Cities are also perfect examples of places where you have these profound wealth inequalities, not just access to money in its direct sense, but access to resources, access to social services, access to disaster relief. There was a pretty shocking study that highlighted the disparity in who received disaster relief. It was upsetting that the disparity followed racial as well as income divides. Cities are an important focal point for understanding how a lot of these things might unfold, because they are unfolding now in front of us.

KS: There are some really important points you make throughout the paper about power, equity, ethics, justice, the connections of environmental justice and equality in the notion of Anthropocene and risk, and a lot of different elements in governance. How important is it to understand the history of how we got to this point in society for understanding Anthropocene risk?

PK: I think history is tremendously important in terms of understanding why we find ourselves in the places that we do now. Maybe it’s outside of the scope of what’s been expected of natural sciences, but history matters because it creates the map that we see now. Bananas don’t grow in Colorado, let alone most of the United States. I get them from this global economy. But it exists because of certain historical, economic factors that created these patterns of trade, and will continue to do so.

If we zoom out, we can go to another place and look at the fisheries trade and the contemporary slavery on offshore fishing vessels. This egregious state of affairs still exists while we’re talking on the phone. It’s happening right now. And the question is, would that be the case if it were happening to, say, people in Sweden? Most likely not. If it even emerged, it would probably be dealt with much more quickly and in a direct, severe way. But it’s not, and we’re still buying food that’s probably coming from that part of the world. There is tremendous work in developing traceability and other forms of understanding, improving the transparency of a lot of these global commodities or have fish shipping from. But there still is obviously a long way to go.

We have a global economic system that is built on historical power structures, such as colonialism, that we continue to feel ricocheting effects into our modern era. The US is wealthy for lots of reasons, some of which can be traced directly back to the US’ role as a gigantic consumer of African slaves. Our early economic wealth as a country was very much due to the free expendable labor of other humans. This ugly truth, and other truths like it, must be considered as contributory to Anthropocene risk.

So if we want to address some of these problems, we also have to address the problems that we still have and we have not addressed yet. That’s all intertwined. Whether it be racial injustice, whether it be addressing slave fleets in another country, whether it be the ability of certain companies to pollute without consequence in one place. And so they go there and do that and impact those communities. But then that doesn’t have any sort of feedback to the consumers of that product. All of those things are complex and there’s no easy solution necessarily because our system is designed to operate that way.

In my role as a research scientist, I tried to examine these situations from a different perspective, and the big Anthropocene risk is that if we don’t create social change and address the inequities and environmental justice issues along with all the actual geophysical changes we’re making, we’re not going to “solve” the bigger problems going on.

DATE

September 9, 2019AUTHOR

Kelsey SimpkinsPatrick Keys

SHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Future Earth Members Selected as Experts for IPCC Special Report on Cities

Sign the COP28 statement. The Science is Clear: We Need Net Zero Carbon Dioxide Emissions by 2050.

Unmasking our Carbon and Climate Futures