Scientists assemble most complete database of greenhouse gases to date

Think of it as the encyclopedia of greenhouse gases: International scientists have assembled the most complete database in the world of the gases in the atmosphere that cause climate change. The effort will be critical in helping researchers to better understand the local impact of climate change in regions around the world, the team says.

The new database was published this week in the journal Geoscientific Model Development. It’s an exhaustive effort, bringing together “millions and millions of data points,” says lead author Malte Meinshausen. He is head of the Climate and Energy College at the University of Melbourne in Australia. These data points, he explains, provide a detailed view of the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the air over time – capturing not just how they changed from year-to-year but also how they differed in distinct parts of the world and between seasons.

And the study goes beyond the usual suspects, too: While the team’s database includes detailed records for household names like carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, it also captures data for 40 other gases – each of which has a small, but not insignificant, impact on the planet’s climate. They include more obscure chemicals with names like Halon-1301, a fire suppression chemical, and sulfuryl fluoride, used as a grain and timber fumigant.

The study underscores just how important basic data are for understanding the future of climate change, says study co-author Pep Canadell.

It’s critical “so that we can do more than just come up with the mean change of global temperatures. We can also make conclusions that are as meaningful and accurate as possible at the regional level,” says Canadell, executive director of the Global Carbon Project, a research project of Future Earth. People “don’t particularly care about the mean global temperature. People care about the temperature change in the place they live.”

Deep dive

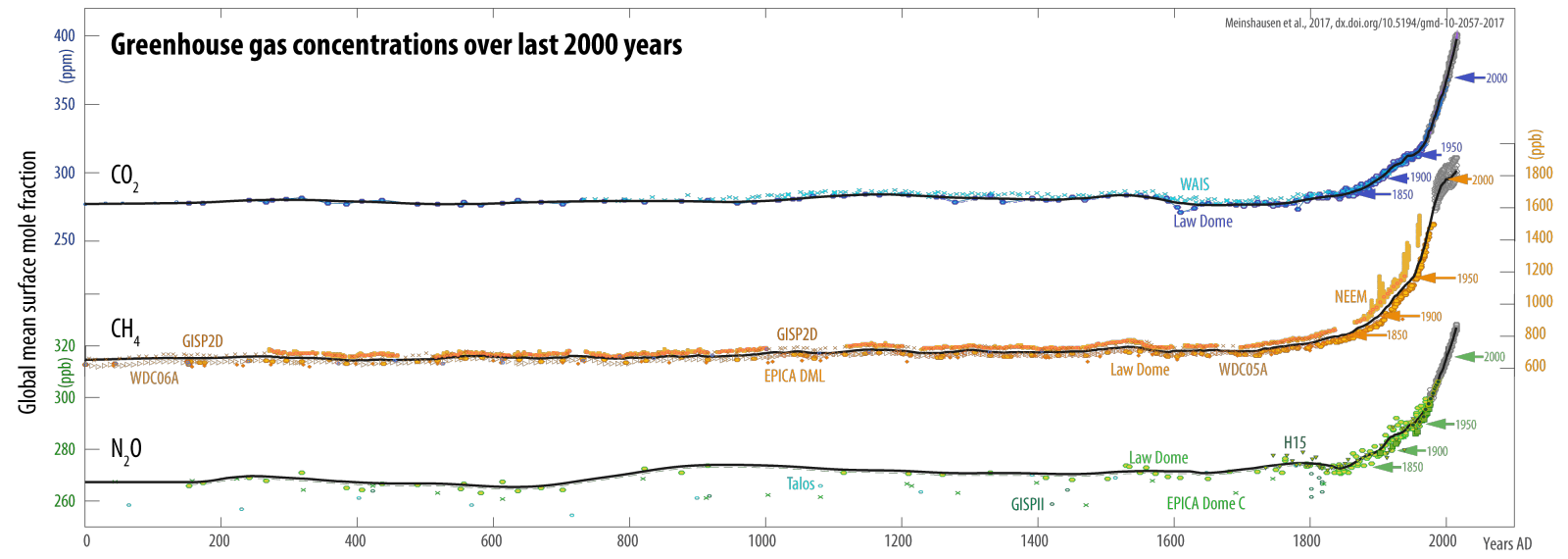

To reach people in the places they live, Meinshausen, Canadell and their colleagues pulled data from a wide variety of sources. They looked, for example, at observations of atmospheric composition collected by stations around the world – such as on the top of Mauna Loa, a volcano in Hawaii, United States, and from Cape Grim on the west coast of the Australian island of Tasmania. They also turned to records of past greenhouse gas concentrations, including air samples collected from bubbles trapped in ice. The researchers’ final database extends back at least 100 years and, for some gases, as far back as the last 2000 years.

It’s a deep dive, which Canadell says is critical. The data will eventually be included in projections of future climate change used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the world’s leading body on climate science.

Researchers recreated a 2000-year history of the concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) in the atmosphere. Graphic: Meinshausen et al. 2017.

And to make sure that those projections are as accurate as possible, the database assembles records on 43 greenhouse gases – 17 more than were included in earlier efforts of this kind. Many of those gases are produced only by humans and were never seen in the air until after the Industrial Revolution.

“It’s incredible to think that we have actually produced from scratch through all sorts of industrial processes these gases that do not exist in nature and are now affecting the climate,” says Canadell, who is also a research scientist at the Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

Most of the lesser-known greenhouse gases are also ozone depleting substances, which are the third largest contributor to climate change after carbon dioxide and methane. Like those gases, ozone depleting substances can trap heat in the atmosphere. But as their name suggests, they can also eat away at the planet’s ozone layer, causing holes like the one that formed above Antarctica in the last quarter of the 20th Century. They include dichlorodifluoromethane (CFC-12), which was formerly used as a refrigerant and in aerosol sprays, and chlorodifluoromethane (HCFC-12), which can still be found in many air conditioners.

Together, the ozone depleting substances are responsible for a big fraction of the warming that scientists have seen in the industrial era – roughly 13%. Carbon dioxide, in contrast, drives 64%. However, unlike carbon dioxide, the ozone depleting substances are as a group declining in the atmosphere. Many of these gases were phased out of use by an international treaty called the Montreal Protocol, originally signed in 1987.

“This makes the Montreal Protocol the most successful international climate change mitigation agreement to date,” says Paul Fraser, a research scientist at CSIRO and co-author of the study.

Canadell adds that this success shows that there are many different ways for nations to slow warming temperatures. “As we move toward addressing climate change through mitigation, these are all opportunities that give us flexibility and give us extra leverage to make an impact,” he says.

Meinshausen agrees but says that carbon dioxide should still be the world’s priority. “Once we get CO2 under control, and we have to get that under control, … then the other gases also become very important,” he says. “Because if we don't get a handle on these other gases, we still might not be able to keep the warming as low as we can.”

Data under threat

Meinshausen notes that many programmes for gathering basic data relevant to climate change are now under threat – the causality of funding cuts around the world. CSIRO announced a wave of job cuts in 2016, for example, after the Australian government slashed its budget. U.S. President Donald Trump has also proposed major reductions to the 2018 budget of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The administration operates the world’s largest global greenhouse gas monitoring network, including the station on Mauna Loa.

And those have the potential to be major losses. The reason why comes down to two words, says Fraser: “Verification, verification.” He helped to launch the air monitoring station at Cape Grim in Australia in the 1970s. He paraphrases a U.S. colleague who said that “greenhouse gas emissions regulations without atmospheric verification is like dieting without weighing oneself.” In other words, how can you know that efforts to reduce greenhouse gases are working if you stop checking the air?

Greenhouse gas monitoring may not be as flashy as new scientific findings, Meinshausen says. But it's central to climate research like the new database that he and his colleagues have assembled. “We’ve only done the last 10 centimetres after a marathon of these decades of efforts,” he says. It’s really a lot of people’s lifetimes that go into these measurements.”

DATE

May 31, 2017AUTHOR

Daniel StrainSHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Spotlight on LMICs – Tired of Breathing in Pollutants? Time for Better Fuel Economy and Vehicle Standards

Future Earth Taipei Holds 2024 Annual Symposium

Spotlight on LMICs – The Future’s Juggernaut: Positioning Research as Anchors for Environmental Health