The impact of Cotton aid and agricultural subsidies on water resources in Thessaly, Greece

|

The Water-Energy-Food Nexus Blog Series Delivering water, energy and food for all in a sustainable and equitable way is a major challenge faced by society. The water-energy-food nexus concept aims to address this by better understanding how interactions between water, energy and food are shaped by environmental, economic, social and political changes and how the synergies and trade-offs among them can be better planned and managed. The Water-Energy-Food Nexus Knowledge-Action Network is a network of people and organisations which fosters transdisciplinary research and communicates the importance of holistic system approaches across water, energy and food systems. Acknowledging that the nexus concept is often described as overly academic and not practical on the ground, the Water-Energy-Food Nexus Knowledge-Action Network is organising this blog series to illustrate the role of the nexus concept in addressing local and national challenges of sustainable and equitable access to resources. Understanding the perceptions and entry points with which local and national stakeholders can engage with the nexus concept is key to further implementing nexus approaches, especially in the Global South. Learn more about the Future Earth Water-Energy-Food Nexus Knowledge-Action Network. |

The impact of “cotton aid” and agricultural subsidies on water resources in Thessaly, Greece

By Chrysi Laspidou

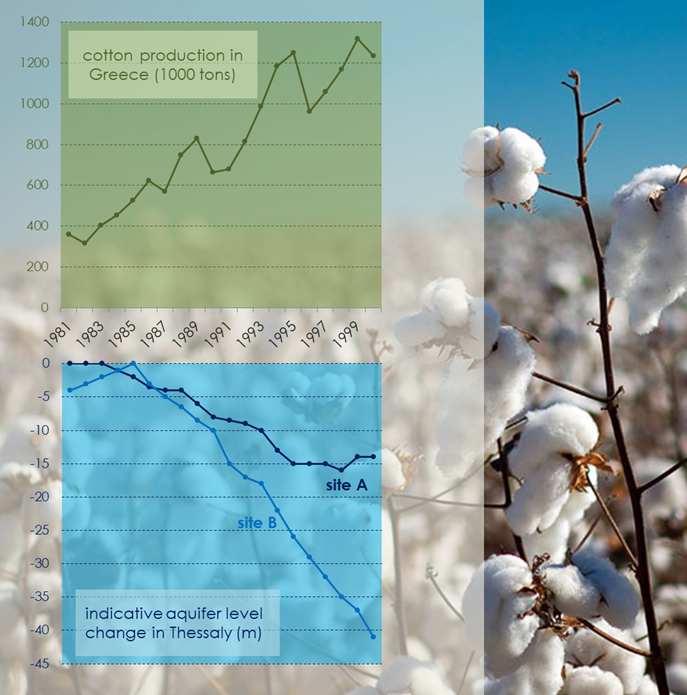

A series of European agricultural subsidies to cotton farmers, known as Cotton aid, was introduced in 1981 by the European Economic Community, with the accession of Greece to the community. This marked the beginning of a series of European and National policies that resulted in the heavy subsidization of cotton production at various levels, including subsidies for farmers, for machinery and for the cotton ginning industry. Currently, cotton is produced in Europe on around 300,000 hectares. Greece—mainly the region of Thessaly—is the main cotton grower, accounting for 80 percent of European cotton area and 85 percent, or 230,000 tons, of European production. It is thanks to Cotton aid that this industrial crop is so heavily cultivated on the Thessaly plain, which is the most intensively cultivated agricultural plain in Greece.

Unfortunately, cotton requires large amounts of water for irrigation. In Greece, this creates a strongly seasonal water deficit that peaks during the summer months, when precipitation is at its lowest. According to the Greek Ministry of Environment and Energy, the water resources in the Thessaly River Basin District are “bad” in terms of both quantity and quality, with a large deficit in surface and groundwater resources and groundwater nitrate concentrations often higher than 50 ppm. The water table in Thessaly is dropping fast; farmers need to drill down to as far as 250 metres to find water. Seawater intrusion and groundwater salinization are a reality throughout the plain, decreasing the quality and potential usability of the water in the years to come. Furthermore, the effects of land subsidence, due to groundwater depletion, on people’s properties and lives is evident throughout Thessaly. In addition, the Pinios River, a major Greek river that runs through Thessaly and is tightly connected with the local community and traditions, often dries up during the hot summer months, when farmers use most of its flow for irrigation.

Credit: Chrysi Laspidou

Cotton production takes up agricultural land and is extremely resource intensive, without enhancing regional or national food security. To make things worse, the Greek government provides energy subsidies for irrigation to farmers to boost agriculture and food production. As a result, farmers are still able to afford to cultivate cotton in Thessaly. The farmers are not motivated to move to more energy-efficient irrigation systems, as they pay over 30 percent less for electricity than their household counterparts. As the water table drops, pumping becomes even more energy-intensive, further driving the vicious cycle of policies which are not coherent with the nexus concept. Moreover, as agricultural water in Greece is provided free-of-charge to farmers, there are no incentives for the farmers to minimize water losses. As a result, they continue using sprinkler irrigation and other methods which are not suitable for the local conditions, such as water scarcity, extensive droughts and threatening desertification. Agricultural water-pricing is expected to be a hot topic in Greece in the years to come, with the government now hinting that farmers will have to start paying for water to cover the environmental cost as well.

European policies and subsidies have intensified cotton production in the Thessaly region of Greece—but at what cost? In 2011, 51 percent of irrigation water in Thessaly was used for the irrigation of a single crop: cotton. Furthermore, about 54 percent of the cotton produced is exported. In terms of virtual water embedded in crops, 73 percent of total virtual agricultural water that is exported is due to cotton (Mellios et al., 2018). Policy-makers need to review the capacity of Thessaly’s water resources, in terms of both quality and quantity, to carry such a heavy load. If they recognised the importance of the nexus concept and understood the synergies and trade-offs between the water, energy and food systems, the policy-makers might decide that cotton is probably not the best crop choice for the water-scarce region of Thessaly, especially under the influence of climate change.

DATE

August 6, 2018AUTHOR

Chrysi LaspidouSHARE WITH YOUR NETWORK

RELATED POSTS

Spotlight on LMICs – Tired of Breathing in Pollutants? Time for Better Fuel Economy and Vehicle Standards

Future Earth Taipei Holds 2024 Annual Symposium

Spotlight on LMICs – The Future’s Juggernaut: Positioning Research as Anchors for Environmental Health